What is a grief attack?

Jane Griffin, 71, knew her husband was dying – he had suffered from Lewy body dementia for more than a decade. But she didn’t anticipate the impact her loss in April this year would have on her.

Something small, like seeing one of his favorite foods in the supermarket, could “send me into a downward spiral,” Ms. Griffin said.

She felt unexpectedly tense, her heart racing as a wave of emotions washed over her. “No one could have prepared me for this feeling of extreme fear,” said Ms. Griffin, who lives in Arizona.

She suffered what some researchers call a “grief attack,” a term that has been used for years to describe a sudden surge of overwhelming anxiety rooted in grief. It also has other names: grief, grief spasms or loss panic, to name just a few. While the phenomenon is familiar to therapists and many who have lost a loved one, grief experts are now examining the specific symptoms and circumstances associated with grief attacks and trying to assess their severity, which can range from uncomfortable to debilitating.

“It’s like a panic attack, which is – I can personally attest to this – terrible, but with deep sadness about it and all these symptoms hitting you at the same time,” said Sherman Lee, an associate professor of psychology at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia. “It really is a fascinating phenomenon that really shakes you to the core if you ever experience one.”

What does a grief attack look like?

Dr. Lee is a co-author of a study published in November that surveyed 247 bereaved adults who reported experiencing bouts of grief, nearly half of them once or twice a day.

The study found that grief attacks are often manifested by panic attack symptoms such as shaking, sweating, numbness and dizziness. They were also accompanied by one of the three aspects of grief: longing, despair, or a breakdown of coherent thought.

Grief attacks can occur at any time. They could be triggered by something that brings back memories of a loved one, said Robert A. Neimeyer, the director of the Portland Institute for Loss and Transition in Oregon and Dr. Lee’s co-author. But more often, according to Dr. Neimeyer, they appear unexpectedly in quieter times at home: “Something about loss just happens to us and – boom – the floodgates open.”

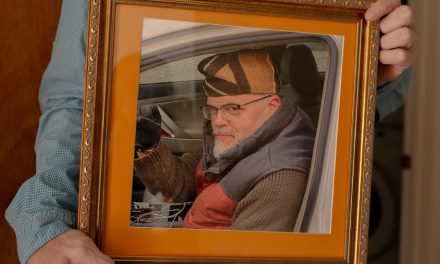

Grief attacks are particularly worrisome, said Dr. Neimeyer, if they put someone in physical danger (e.g. if someone experiences one while driving) or if the grief attacks last too long, do not subside with time, or interfere with a person’s ability to function in daily life.

In less serious cases, although bouts of grief may be difficult and unpleasant in the moment, they generally resolve quickly and may even have positive effects.

How can grief attacks be a good thing?

Therese A. Rando, a clinical psychologist at the Institute for the Study and Treatment of Loss in Warwick, Rhode Island, said grief attacks are a common and potentially therapeutic part of the grief process.

For example, if you’ve been suppressing your grief over the death of a loved one, a bout of grief might cause you to confront the reality “that they’ve passed away,” Dr. Rando. And when a bout of grief brings back memories of a loved one, you may find yourself thinking about different aspects of that loss. For example, when parents come across the year their child would have graduated high school, they may have to mourn that milestone.

Dr. Rando, who lost both parents as a teenager, said she hasn’t had a grief attack in decades but has experienced occasional bouts of grief without symptoms of panic. Last December, when Judy heard Garland singing “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas,” she burst into tears as she thought of her parents.

It felt cathartic to experience “a moment of real sadness about missing these two extraordinary people who were taken from me at such a young age,” she said. “You never fully get over a loss.”

What coping strategies are there?

Coping with a grief attack is similar in some ways to coping with a panic attack, the experts said. Breathing slowly from your stomach can help. This also applies to repetitive physical movements such as stamping your feet.

Linita E. Mathew, a career counselor in Calgary who has written two books about grief, said she experienced frequent bouts of grief after her father’s death nine years ago.

“I had to run to the toilet because I thought I was going to throw up at any moment,” she said. It helped to put her hands under cold running water.

Additionally, “my eyes were moving back and forth,” she said, “as if my eyeballs were shaking or shaking.” She later noticed that when she focused on her father’s image, her eyes became calmer.

Given that grief attacks can be linked to specific triggers, such as a loved one’s possessions, it is also important to develop coping strategies that gradually expose us to these items so that their power diminishes, Dr. Neimeyer.

And often, he added, we must find ways to continue to show our love to those who have died, even in their absence.

The goal is not to keep going, “but to find a way to persevere differently,” he said.